There are tons of films about films, and plenty of music about making music, but a conspicuous lack of games about games. The mark of an immature medium or a lack of mainstream interest in the actual making of games? Probably both, but nobody who’s played it can forget the superb gallows humour of Segagaga, and the door’s open for someone to nail it.

There are tons of films about films, and plenty of music about making music, but a conspicuous lack of games about games. The mark of an immature medium or a lack of mainstream interest in the actual making of games? Probably both, but nobody who’s played it can forget the superb gallows humour of Segagaga, and the door’s open for someone to nail it.

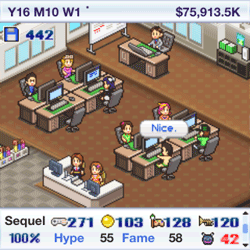

So along comes Game Dev Story, an iPhone simulation of the last 25 years of the games industry. You start with a couple of developers, a handful of genres and settings to choose from, and enough money to develop a game. Make it a success and you can plough funds back into new, increasingly complex games, and as you cultivate a following and begin to establish some commercially viable franchises, generating enough money to buy licences to develop for successive consoles that in no way bear a resemblance to the systems of Nintendo, Sega, Sony and Microsoft. Fail to make it, if that’s possible, and you can bide your time by jobbing on translation projects and porting jobs to make a quick buck.

It’s extremely addictive, and if you have the same affection for gaming in the 80s and 90s as I do, it’ll certainly get its claws into you. But what was more interesting is how it forces you to confront some awkward truths about how this industry works.

Follow the game’s prompts and, sooner or later, you’ll be some kind of mega publisher, every game provoking queues around the block and employing the in-game equivalents of Aaron Sorkin and Lady Gaga to script and score your latest release. But it quickly becomes apparent that the quickest way to the top is to make a couple of hits and then exploit them – that sounds somehow familiar – repeatedly. I’d love to see the Sorkin/Gaga collaboration, but when it’s on a game called Dark Ninja XVIII, it’s not as interesting to me as it could be. And where do you go for the most money after that sells 20 million? Why, Dark Ninja XIX, of course.

Is Game Dev Story some kind of secret Activision PR job, then, intended to get us to see things from the dark side? Or, sadly, just an accurate demonstration of how the games industry really works? I think a look at 2011’s lineup of annual sequels and reboots should answer that.

Depressing as it may be, though, it’s a bloody good little game.

Since the App Store launched, it was only a matter of time before someone got their act together to create the perfect confluence of handheld hardware power and touchscreen-focused game design. Truth be told, there have been a few contenders on iOS this year, but I think this really deserves to be the first.

Since the App Store launched, it was only a matter of time before someone got their act together to create the perfect confluence of handheld hardware power and touchscreen-focused game design. Truth be told, there have been a few contenders on iOS this year, but I think this really deserves to be the first.